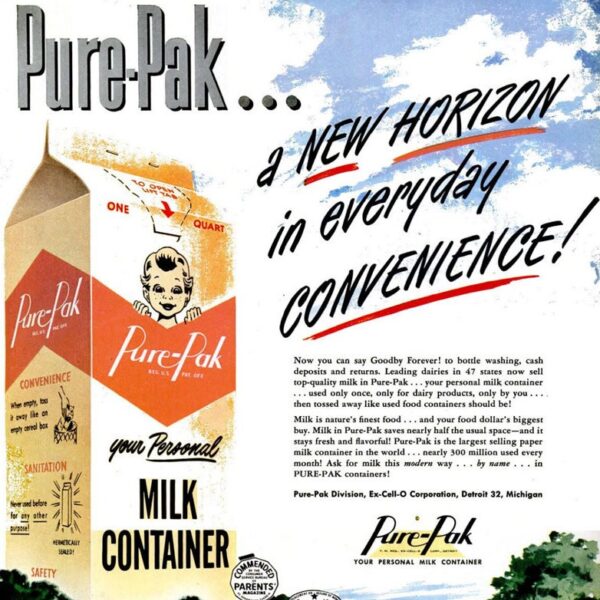

It’s the early 1960s. Girls are fainting over the Beatles, Sean Connery is James Bond and a revolutionary trend is sweeping the United States: Plastic.

Plastic is about to have its breakthrough moment in the food industry. The plastic milk jug, specifically, is on the brink of taking off: the “market potential is huge,” the New York Times correctly notes.

To American families, a third of which are still getting their milk from a milk man, plastic is a wonder package. It’s lighter than glass. It doesn’t break. Unlike paper cartons, it’s translucent. You can see how much liquid is left in the jug. With a plastic container, everybody wins.

Except for the milk man. And, as it would turn out, the planet.

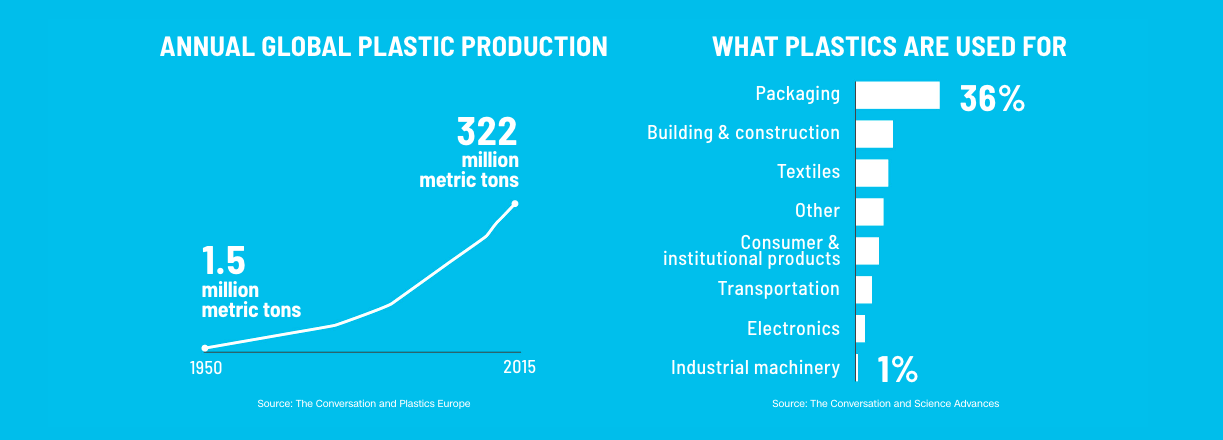

Fast forward to now. Plastics are expected to outweigh fish in the ocean by 2050. Marine life is choking on the debris: Microplastics are in our soil, our water, our air, getting into our bodies with potential consequences that we don't fully understand yet. Massive amounts of plastic have piled up in landfills, some emitting greenhouse gases and contributing to global warming over the seeming eternity they take to degrade. Plastics are threatening the health of the planet and its inhabitants, and they’re not going away.

Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Danone, Mars Petcare, Mondelēz International and others — some of the world’s largest consumer goods companies — are partnering on a potential solution to limit future waste. They’re working together on a project known as Loop, announced at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland on Thursday. It offers consumers an alternative to recycling — a system that isn't working well these days.

At this point, the partners are testing the waters. It’s an experiment they’ll roll out to several thousand consumers in New York and Paris this May, with plans to expand to London later in 2019 and Toronto, Tokyo and San Francisco in 2020.

Mark Kauzlarich for CNN

Loop is a new way to shop, offering about 300 items — from Tide detergent to Pantene shampoo, Häagen-Dazs ice cream to Crest mouthwash — all in reusable packaging. After using the products, customers put the empty containers in a Loop tote on their doorstep. The containers are then picked up by a delivery service, cleaned and refilled, and shipped out to consumers again.

In other words, it’s the 21st century milk man — here to save the world from single-use plastics.

Maybe.

Two years ago, Tom Szaky traveled from Trenton, New Jersey to Davos with a half-baked idea and a loose plan to pitch it to the leaders of the world’s biggest brands.

Szaky, now 37, is the CEO of TerraCycle, a modest waste management company. TerraCycle expects its global 2018 sales to amount to $32 million and is currently trying to raise $25 million from small investors.

A Princeton dropout with big ideas and a casual demeanor, Szaky spent the first years of his career talking about “worm poop,” a phrase he used to market his fertilizer business in a way that got him a ton of media attention. By the time he was 24, he had landed contracts with Walmart and Home Depot. His mission — to eliminate waste first and make a profit second — is so seductive, some employees have taken major pay cuts to work for TerraCycle. The company’s Trenton headquarters is decorated with garbage; Szaky’s office walls are hanging curtains made from empty plastic bottles.

Mark Kauzlarich for CNN

At Davos, he said, a certain vibe made top business leaders amenable to his idea.

“Have you ever been to Burning Man?” Szaky asked during an interview with CNN Business. “The closest comparison —and it’s a weird comparison to me — is going to Burning Man.”

At Burning Man, the annual week-long event where participants build a temporary community in the Nevada desert, people inherently trust each other, he said. At Davos, he was able to approach any business leader and, because of a similar type of openness, be granted an audience.

Szaky was at Davos in 2017 because TerraCycle had helped Procter & Gamble launch a line of Head & Shoulders shampoo that came in bottles made with plastic collected from beaches. While he was there, Szaky — a slick, charismatic pitchman — landed a spot on stage with the CEOs of Walmart, Alibaba and Heineken. He also secured short meetings with the leaders of consumer packaged goods companies and pitched them on his big idea.

Szaky asked companies to think differently about who owns their packaging. Today, companies sell consumers both the product and the package it comes in. Ultimately, it’s up to the customer — and also the municipality where they live — whether an empty bottle gets recycled or tossed in a landfill. Under the current system, the fate of the bottle is out of the manufacturer’s hands, so companies aim to produce the cheapest possible packages, Szaky said.

But what if, instead, the manufacturer retained ownership of the bottle by collecting and reusing it? The company could count it as a longer-term asset on its balance sheet and depreciate it over time. Under that system, the manufacturer would be incentivized to invest more resources in an elegant, durable design, Szaky argued.

At Szaky’s pitch meetings, some important subtext went unsaid. The plastic waste that ends up in landfills and oceans has the logos of the world’s biggest brands all over it. He had specifically targeted companies that were featured on a Greenpeace list of worst plastics polluters, because he knew they had a potential public relations crisis on their hands.

“I don’t have to rub this in their face,” Szaky said, because the companies are “painfully” aware of their reputations.

The consumer goods giants got on board. And after that trip, Szaky got serious about making Loop a reality by Davos 2019.

Now, eight of the 10 companies mentioned in the Greenpeace report are Loop partners.

Loop customers have to make an account and fill up a basket online. The prices for the items should be comparable to what they would be at a nearby store, Szaky said.

In addition to the regular cost of the item, customers must put down a fully refundable deposit for each package. The deposit varies from about 25 cents for a bottle of Coca-Cola to $47 for a Pampers diaper bin (which TerraCycle said eliminates the need for a Diaper Genie). Shipping becomes free after the customer buys about five to seven items, depending on the size and bulk of the products.

In the United States, the items arrive via UPS in a Loop tote bag. Frozen items, like ice cream, come in a cooler within the tote.

As customers go through products — use all the shampoo, eat all the ice cream — they fill up the totes with the empties. Unlike traditional recyclables, the packages don’t need to be washed. At the end of the cycle, a UPS driver picks up the tote. Customers can keep repeating the cycle or opt out and recover their deposit. Even banged up packages earn back the deposit — customers only lose that money if they fail to make a return.

When the packages are no longer suitable for use, TerraCycle recycles them.

Loop may be convenient for users in some ways, but there are potential drawbacks. Szaky acknowledged that it’s a lot to ask people to use yet another retail website. He hopes that Loop will eventually be integrated into existing online shops, including Amazon.

“We’re not trying to harm or cannibalize retailers,” Szaky said. “We’re trying to offer a plug-in that could make them better.”

Already, two large retailers, Carrefour in France and Tesco in the United Kingdom, are Loop partners and more may join the project. Eventually, Loop packages may also be sold on store shelves.

Shoppers who want to be a part of Loop’s soft launch in May have to apply. The first group of users will be selected based on location and overall interest in the platform, according to TerraCycle. The test will allow Loop to iron out any kinks before the program is open to the broader public, Szaky said.

Partner companies have to pay to participate in Loop. Szaky didn’t disclose the buy-in amount, but said it’s in the low six figures. On top of that, many are redesigning their traditional packages — an expensive endeavor that could cost another seven figures, Szaky said.

Szaky said TerraCycle asked the Loop partners to design packages that can survive at least 100 reuses. Rick Zultner, TerraCycle’s director of product and process development, is more measured; he called that figure a “nice goal to meet.”

“Some things can definitely meet that,” Zultner said, adding that if the packages are reused at least 10 times, they’re probably still better for the environment than single-use plastics.

TerraCycle needs to conduct its beta test to make sure that hypotheses like these are right. “There is a fundamental advantage of reuse versus recycle,” Virginie Helias, Procter & Gamble’s chief sustainability officer, said. But “we need to have certain conditions” to make it work, she added.

Carbon emissions from trucking and other factors could outweigh the environmental benefits of Loop if packages are only reused a few times, or if the transportation system is too spread out. Loop has conducted life-cycle analyses to try to estimate the environmental impact in a variety of situations.

To maximize the number of reuses, Loop packages are made out of durable materials like stainless steel, aluminum, glass and engineered plastic, which is stronger than disposable plastic.

Loop packages are sleek and innovative. Degree’s refillable deodorant in silver and white looks like something Apple would make. Ingredients and, when relevant, nutritional information for all products appear in an insert inside the Loop tote instead of on the packages.

One package — a bin launched by Procter & Gamble in the Paris test — is designed to hold soiled Pampers diapers and Always menstrual pads. It has a carbon filter to block odors. The hygiene items, which are traditionally thrown out, are instead recycled, while the bin is sanitized and sent out again.

Nestlé’s new Häagen-Dazs container, part of the New York launch, is designed to keep ice cream cool in the Loop tote and cooler for 24 to 36 hours.

Procter & Gamble

Kim Peddle-Rguem, president of Nestlé’s US ice cream division, called the redesign a “torture test.” It took 15 tries to get the container, a double-walled stainless steel vessel, right. In one prototype, the ice cream wouldn’t harden at a critical stage. Another package was too difficult for customers to open.

For now, Nestlé is making 20,000 containers for the Loop test. Five flavors will be available: Strawberry, vanilla, non-dairy chocolate salted fudge truffle, non-dairy coconut caramel and non-dairy mocha chocolate cookie.

Brinson+Banks for CNN

Because the test is so small, Nestlé isn’t making Loop products in any other facility — which means it has to truck everything from California to the East Coast. If the project takes off, Nestlé will rethink that route to make sure it’s environmentally sound.

“This process isn’t yet perfect and we know it will need to continue to be updated and refined,” said Peddle-Rguem. “We will be analyzing all parts of the process, including shipping and how many times consumers are reusing the container to find those areas for adjustment.”

Consumer goods companies say their customers are demanding more environmentally-friendly packaging.

“We’re seeing that very clearly in our research,” said Procter & Gamble’s Helias, adding that wasteful packaging is “becoming a deterrent for purchase.”

Mondelēz, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, Unilever and others are aiming to make all or some of their packaging out of recycled materials by 2025. Szaky doesn’t think they’ll be able to pull it off.

CNN

“Recycling is a failing industry,” he said.

Roughly 30% of US recyclables are exported overseas. But in 2017, China — then the world’s largest importer of waste and scrap — stopped accepting unsorted paper and some types of plastic from other countries, throwing the US recycling system into a tailspin.

The Chinese ban left many communities scrambling for a new place to send their recyclable waste. Some municipalities halted curbside pickup for recycling, others recycled fewer items or raised prices. The operators of some recycling facilities reportedly stashed recyclable waste, looking for a new buyer, but ultimately dumped it in landfills.

Unaware consumers may continue as usual, without realizing their recyclables aren’t being recycled at all.

Last year, “we saw a global shift in how recycling works,” said Keefe Harrison, CEO of The Recycling Partnership, a nonprofit group that uses corporate funding to help develop recycling infrastructure.

China’s ban is not the only reason that recycling is struggling. Ironically, an effort to reduce packaging called lightweighting — making plastic packages, like water bottles, lighter as a way to use less plastic and reduce the amount of fuel needed to move packages by truck — poses recycling challenges because light packages fly off recycling conveyor belts and get lost.

Plus, low oil prices make it cheaper for companies to just make plastic from scratch, Szaky noted.

Overall, about 91% of all the plastic waste ever created has never been recycled — a statistic so “concerning,” the Royal Statistical Society named it the 2018 international statistic of the year.

Recycling is not the best way to cut down on waste. “Preventing in the first place is always better than cleaning up after,” Harrison noted.

If Loop works correctly, it would do just that. The question is: will it work?

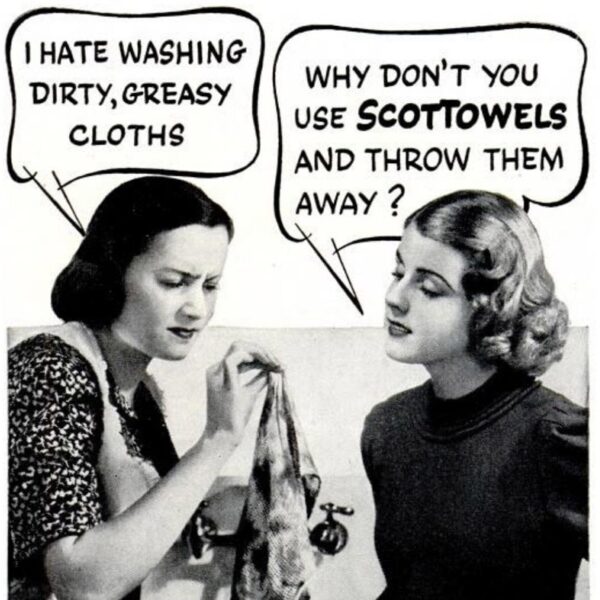

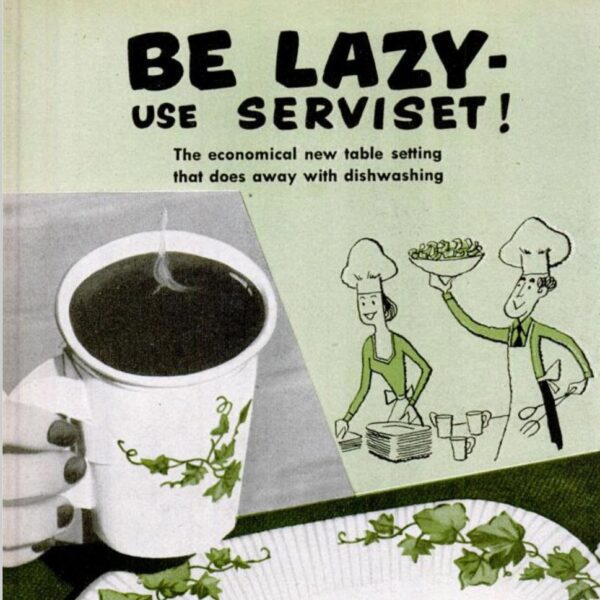

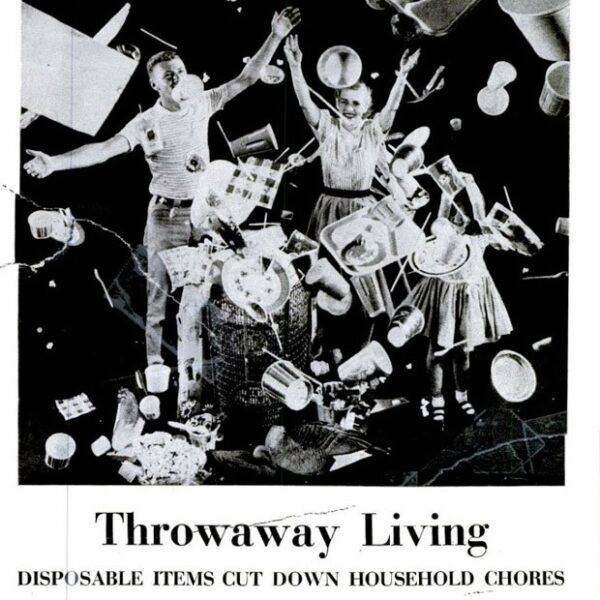

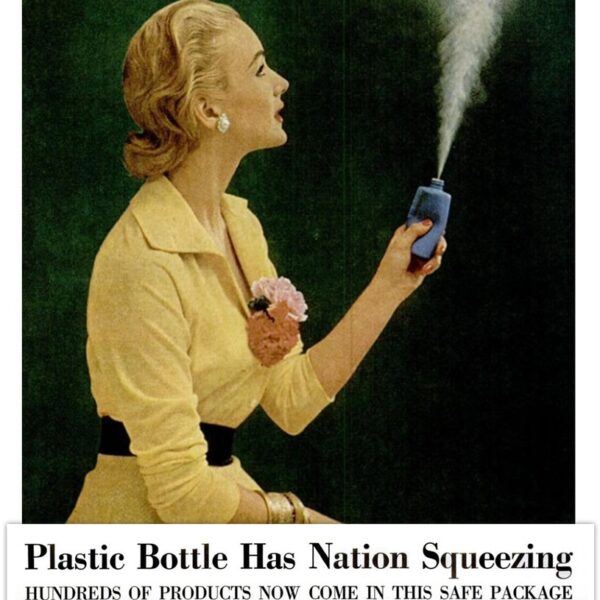

Single-use packages were touted as convenient and elegant in mainstream media from the 1930s to 1960s.

For the largest players, Loop is a relatively small experiment. The partners are among the largest advertisers in the world. If they wanted to, they could throw their full weight behind promoting reusable packaging. But at this point, the companies are moving forward with caution and pointing to Loop as one part of their broader sustainability efforts.

After about 12 weeks, Nestlé will have a good idea of how and whether to expand the program. Regardless of what the data shows, the company will service Loop customers for at least a year. Unilever said it will evaluate the project over the course of about 12 months.

“We want to put an end to the current ‘take-make-dispose’ culture and are committed to taking big steps towards designing our products for re-use,” Alan Jope, CEO of Unilever, said in a statement. Unilever is testing nine brands in the Loop launch, including Axe, Dove and Degree deodorants, Hellmann’s mayonnaise and Seventh Generation soaps. Like Nestlé, the company will evaluate the project’s success by tracking the number of repeat customers.

We’re “not yet worried about the financial side of this,” said David Blanchard, Unilever’s chief research and development officer, noting the company is more interested in evaluating whether Loop triggers a “behavior change” among some consumers.

It’s easy to see how Loop could fail.

It asks customers to completely rethink how they shop. It asks them to dole out deposit money upfront, something many people can’t afford to do. It assumes that, all things being equal, people prefer their detergent in a spiffy container and their deodorant in a sleek pod. In reality, people may not care. Loop could be a dreamy, idealistic house of cards.

But it also could work.

Small dairies throughout the country are already reviving the milk man by offering delivery services. And it’s not just milk. Refillable beer growlers are staging a comeback, with Whole Foods and Kroger offering in-store beer taps. Startups are trying to help people refill reusable soap containers at home, and millions of consumers are already refilling SodaStream bottles in their kitchens, a sign that there’s a market for reusable bottles.

If there’s ever a time that these new models can succeed, it’s now, said Bridget Croke, who leads external affairs for Closed Loop Partners, which invests in recycling technologies and sustainable consumer goods. (Despite the similar name, Closed Loop Partners has no formal relationship with TerraCycle’s Loop project.)

Getty Images / Loop / CNN

To make Loop work, she added, TerraCycle will “need the right investments, the right consumer goods partners.” And “they’re going to really need to understand how to make the consumer experience better than what they have today.” And with so many big companies on board, they have a “solid shot,” she said.

If TerraCycle manages to find a solution to plastics pollution — to dust off the milk man, spruce him up, give him a website and get people to shop — things will start to change. “Once these trends start to shift,” Croke noted, “then it starts to catch fire.”

Szaky hopes that by the 2060s — a century after plastics came on the food scene — things will have come full circle.

“Hopefully 50 years from now,” Szaky said, “we look at waste as a strange anomaly and we’re happy it’s over.”